PeB Journal | Articles, Conflict Resolution, Europe, General, International Politics

By Anna Luisa Araujo Mendes

In 1995, the Dayton Agreement marked the end of the Bosnian conflict, defining parameters and structures for this newly independent state. However, the agreement was strongly criticized by several researchers for having the opposite effect, that is, instead of helping to integrate the three main ethnic groups in the territory (Serbs, Bosnians, and Croats), the agreement fostered their separation. In addition, it is notable that the establishment of a triple leadership model (the country has three presidents, one of each ethnicity), ended up creating obstacles for decision-making in the country. This article aims to reflect on the consequences of the Dayton Agreement for modern Bosnia. 25 years after its signing, it is possible to analyze some variables and indicators that confirm the positive or negative effects of the agreement for the country.

The Bosnian War

The Balkans region has seen the dominance of several empires throughout history – from the Ottoman Empire, which expanded Islam throughout this territorial area, to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which spread Christianity to various locations. The Bosnian conflict, which was developed between 1992 and 1995, was a consequence of the singularities of this territory, as a result of years under the influence of these empires. Moreover, the Serbian nationalist and expansionist campaing that aimed at the unification of ethnically Serbian territories to constitute the “Great Serbia”, was also another important factor to understand this conflict (Valença 2010).

That being said, with the fall of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War, Yugoslavia was formed, which brought together, under a single government, the current territories of Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro and North Macedonia. In 1941, Yugoslavia was invaded and dominated by the Germans and, as a result, the region came to be administered partly by Germany and partly by Italy. However, in 1943, an anti-fascist coalition led by Marshal Josip Tito proclaimed the Republic of Yugoslavia, which in 1944 expelled the Germans and their allies from the country. In 1945, Tito was elected the leader of Yugoslavia, with the main goal of establishing a provisional government, and to create a new constitution for the country (Gonçalves 2009).

Tito was an important figure for the unification and relative peace of the country from 1950 to 1980, the year of his death. According to Valença (2010, p. 256) “Tito’s death created a vacuum in Yugoslav power. The president who succeeded him was not able to control political institutions, fragmenting the bases for sustaining power”. Soon after, separatist movements in the Kosovo region and economic dissatisfaction in the region of Slovenia and Croatia began to grow. In addition, dissatisfaction with the growing movement in Greater Serbia culminated in an internal Yugoslav crisis in 1989, which reached its climax in Slovenia’s 1991 declaration of independence, followed by Croatia. Bosnian independence occurred in 1992 (Olic 1995; Gonçalves 2009).

Since its independence, Bosnia has faced resistance from its neighbors, Serbia and Croatia, and the development of the conflict over the years has shown its violence and brutality. One of the especially violent crimes committed during this time was the massacre that took place in the city of Srebrenica, where, in July of 1995, more than 7,000 Bosnian Muslims were executed. This event was characterized as the greatest ethnic cleansing in Europe since the holocaust during the Second World War (Gunter 2017).

The Dayton Agreement and its Pillars

The end of the conflict occurred with the signing of the Dayton Agreement in 1995, which did not recognize any party as victors of the conflict and affirmed its commitment to the development of peace and stability in the country. In addition, the Agreement established the continuity of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a single state and the continuity of its borders, but it was to be composed of two entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a majority of Croats and Bosnians, and the Republika Srpska, with a Serb majority (Dayton Agreement 1995).

In order to integrate the ethnic groups and prevent the re-emergence of conflict, a Parliamentary Assembly was created consisting of two houses: the House of the People, composed of 15 delegates, being ⅔ of the Federation and ⅓ of the Republic Srpska, in which each delegate should be elected in their respective region of origin, and the House of Representatives, composed of 42 members, ⅔ elected from the Federation and ⅓ from the Republic Srpska. Decisions regarding the country’s legislation have to be accepted by both houses. In addition, the agreement established that the country’s presidency would consist of three members, one Bosnian, one Croat and one Serb – the first two elected by the Federation and the third by Republika Srpska (Dayton Agreement 1995).

It is noted that the Dayton Agreement had ambitious intentions to establish a new state in a multi-ethnic place that had just emerged from a bloody war. The aim was to create bases for a democratic State, with an economic market and capable of integrating the ethnic groups present in the territory. This was the solution found by the international mediators to maintain territorial integrity while it was possible to end the conflict. However, the development of this agreement is highly criticized, since more than twenty-five years later, Bosnia still has social and economic problems, in addition to being unable to bring together and integrate the present ethnic groups. In the view of the non-governmental organization Minority Rights Group International (2015, p.3) “Dayton peace agreements might have helped to stop the conflict but created a discriminatory and dysfunctional institutional framework that entrenched the marginalization of minority communities and led to broad deprivations of their rights”.

According to Benková (2016), even after years of the agreement, the country remains strongly ethnically divided, mainly between the two entities, which are still fostered by nationalist parties and leaders who preach the sovereignty of one group over another. In addition, politically speaking, it is difficult to find a consensus in Bosnia, mainly because each entity has relative independence for administrative decision-making. Also, the fact that the country has three presidents corroborates the slowness of the administrative and governance process.

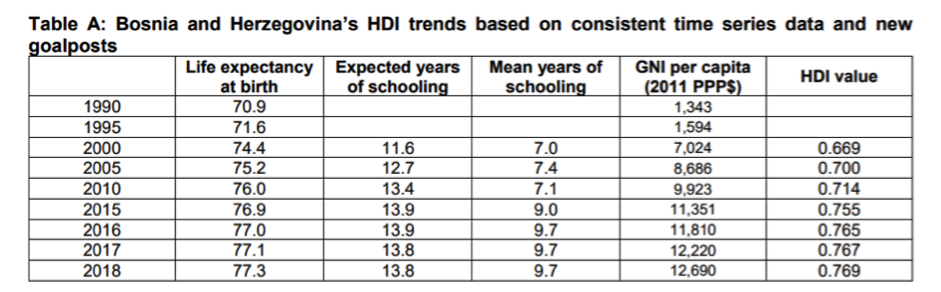

However, when talking about economic and social indicators, improvement can be recognized over the years. According to the 2019 United Nations Human Development Report, Bosnian indicators have improved since the 2000s, notably the Human Development Index and the Gross National Income per capita (which has almost doubled). In the table below, extracted from the report, it is possible to observe such data:

Despite this, while there have been improvements in some sectors; unemployment is one of the main problems in the country. The rate of unemployed young people reached 39% in 2019 – despite the high number, it is still an improvement compared to 2015, for example, when this percentage reached 60% (World Bank 2019). In addition, corruption is an issue in the country; according to the organization Transparency International (2019), Bosnia occupies the 101st position out of 180 in the ranking, while its neighbors, Croatia and Slovenia, occupy the 63rd and 35th position, respectively. This demonstrates that corruption is also one of the obstacles to development and advancement for the country.

Conclusion

Given the above, it can be seen that since the end of the Bosnian War much has been discussed about the effects of the Dayton Agreement for the country – economically, politically and socially. While, on one hand, the agreement fostered ethnic separation through the creation of two administrative entities and the establishment of three presidents, causing the political process to slow down considerably, it is possible to notice a considerable advance in the HDI and life expectancy.

However, other economic problems, such as unemployment and corruption, demonstrate that although the document put an end to the conflict, at the time it was established, it did not provide all the answers for the country’s development. Therefore, one of the great obstacles of the Bosnian State today is the lack of effective and efficient governance, capable of breaking through ethnic separations and helping to improve the country prospects by overcoming the imposed structure of the Dayton Agreement.

About the author

Anna Luisa Araujo Mendes is currently in her fourth year at PUC Minas University, pursuing an undergraduate degree in International Relations. Her area of interest is long-term peace, such as in the context of the Bosnian War. Her undergraduate thesis is about the construction of long-term peace in Côte d’Ivoire and the importance of involving local actors.

Bibliography

Benková, L. (2016). The Dayton Agreement Then and Now. Fokus, Austria Institut Für Europa-und Sicherheitspolitik. Available from: https://www.aies.at/download/2016/AIES-Fokus-2016-07.pdf

Dayton Agreement. (1995). General Framework Agreement for peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina. United Nations. Available from: https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/BA_951121_DaytonAgreement.pdf

Gonçalves, D. (2009). Intervenção da OTAN nos Balcãs: um estudo de caso sobre a redefinição da regra da soberania implícita nos esforços de ordenamento e estabilização. São Paulo, PUC/SP. Available from: https://tede2.pucsp.br/bitstream/handle/4075/1/Daniela%20Norcia%20Goncalves.pdf

Gunter, J. (2017). Ratko Mladic, the ‘Butcher of Bosnia’. BBC NEWS. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-13559597

Minority Rights Group International. (2015). Collateral Damage of the Dayton Peace Agreement: Discrimination Against Minorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Twenty Years On. London. Available from: https://minorityrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/MRG_Brief_Bosnia_ENG_Dec15.pdf.

OLIC, N. (1995). A Desintegração do Leste. São Paulo: Editora Moderna.

Transparency International. (2019). Bosnia and Herzegovina. Corruption Perceptions Index 2019. Available from: https://www.transparency.org/country/BIH#

United Nations Development Programme. (2019). Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century. United Nations. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/BIH.pdf

Valença, M. (2010). Novas Guerras, Estudos para a Paz e Escola de Copenhague: uma contribuição para o resgate da violência pela Segurança. Rio de Janeiro, PUC/RJ. Available from: https://www.maxwell.vrac.puc-rio.br/16533/16533_1.PDF

World Bank. (2019). Bosnia and Herzegovina. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/bosnia-and-herzegovina?view=chart