Pax et Bellum | Alessandro Fava, Civil Wars, Europe, International Politics, Opinions |

Brexit will be one of the most important political events in Europe after the end of the Cold War. The changes for the United Kingdom and the European Union will be massive. Moreover, the United Kingdom will also face challenges from the inside coming from the peripheral regions that voted “Remain”. Northern Ireland with its war-torn history is among them. The Good Friday Agreement that ended the thirty years of conflict, so-called The Troubles (1968-1998), is now at risk.

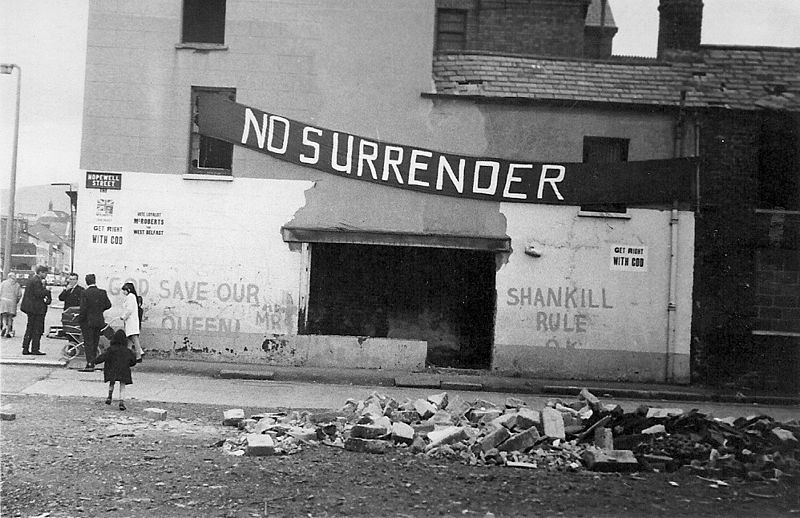

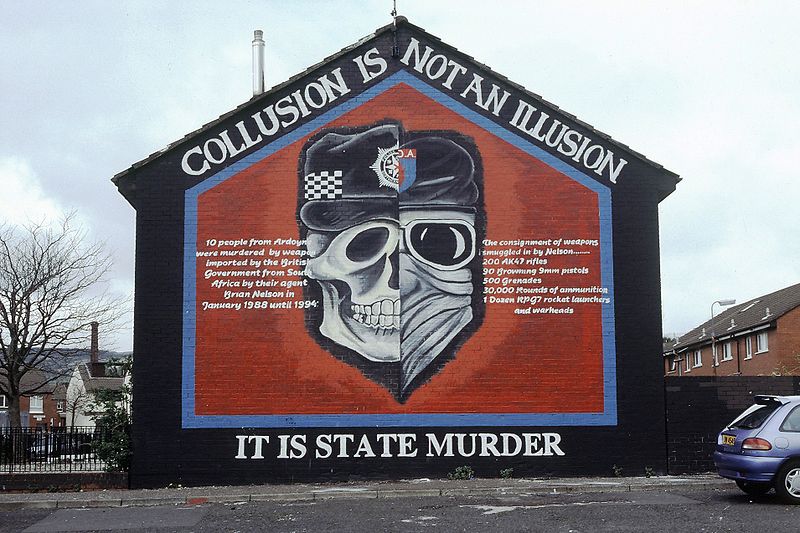

Northern Ireland has all the characteristics to be called the “Balkans of Western Europe”. Sectarian violence along ethnic and religious lines together with a deep-rooted history of conflicts and uprisings has made this region the most unstable of Western Europe throughout the second half of the 20th century. In a period when Western Europe saw one of the most peaceful times of its entire history, in Belfast killings and bombs were everyday news.

The division between the two groups of Catholics and Protestants traces back to the 1600s when the “Plantation of Ireland”, with the arrival of thousands of Scottish (Presbyterian) and English (Anglican) colonists, began. The newcomers concentrated mainly in Norther Ireland where they became the majority of the population. As is the case with many identity construction processes, with the two mainstream Northern Irish ones included, narratives are partly based on historical inaccuracies. For example, the mainstream idea that the Catholics correspond to the native Gaelic population of Ireland is not totally true. In this case, it is often forgotten that many Catholic foreigners, especially Vikings and English, came to the island before the 1600s. On the other hand, the idea that the Protestant front was always united is also inaccurate. In fact, the Scottish Presbyterians sided with the Catholics against the English-ruled government in Ireland for a long period, for example during the Irish rebellion in 1798 (Lundy, 2007).

In 1922 the histories of Ireland and Northern Ireland diverged. With the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Ireland became independent while Northern Ireland remained with the United Kingdom. The partition created tensions in the newly born Irish Free State and a civil war (1922-1923) between the factions supporting and refusing the treaty erupted. Still today, the two main political Irish parties have their roots in the factions fighting in the civil war (Fine Gael for Pro-Treaty and Fianna Fáil against it). The Pro-Treaty faction won the war but Ireland did not recognize the British rule over Northern Ireland until 1998. The violence stopped in the southern part of the island but in 1968 a new conflict in the northern part, commonly known as The Troubles, started. The war lasted thirty years, causing around 3,500 deaths (CAIN, 2017), and came to a conclusion when the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998.

So, what is the Good Friday Agreement and why is it in danger? The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) was signed on April 10th 1998 by the British government led by Tony Blair, the Irish government and the majority of the Northern Irish political parties including the Republican Catholic Sinn Féin (and its military wing, the Provisional IRA) and the Loyalist Protestant parties (with their paramilitary forces such as the Red Hand Commando and the Ulster Volunteer Force). The agreement at its core established local autonomy for Northern Ireland, a power-sharing agreement between the two sides, the disarmament and demobilization of the paramilitary groups and the renounce of Ireland on its claim (that was written in the Irish Constitution) on the north of the island.

At the end of January 2017, Gerry Adams, the historic leader of the Sinn Féin, declared that “Brexit will destroy the Good Friday Agreement” (Mchugh, 2017) and, honestly, he is not completely wrong. Considering that Brexit, scheduled on 29th March 2017 (Ashtana, Boffey and Elgot, 2017), is imminent, what will be the likely consequences?

First of all, the open borders that now exist between Ireland and the United Kingdom, in theory, will cease to exist. The fact that you can travel from Belfast to Cork without being stopped by a British official is extremely important for the Irish people on both sides. A new border between the European Union and the UK (especially in the case of hard Brexit) will make everything more difficult.

Secondly, there is the issue related to the Irish citizenship. According to the GFA, the people of Northern Ireland can choose their citizenship: only Irish, only British or both. Although the number of people choosing the first option is small, the Catholic population is entitled to have just the Irish citizenship. With the UK inside the EU, the problem was easily solved thanks to the freedoms connected to the European citizenship but from now on the situation can become more problematic and a solution for those who do not want the British citizenship has to be found.

Thirdly, there is also a human rights issue. The GFA affirmed that the respect of the human rights in Northern Ireland is under the jurisdiction of the European Convention on Human Rights (that is not part of the EU institutions but the EU is a member of the Convention). The problem is that the British Prime Minister Theresa May declared before Brexit that the UK should leave the Convention (Ashtana & Mason, 2016) and there are rumors that she is actually planning to put the issue on the table at the next election in 2020 (Worley, 2016).

There are other aspects that could increase the grievances in the region. In addition to the fact that Brexit was not approved in Northern Ireland (56% Remain vs 44% Leave), the region received a huge financial help from the European Union. To be more precise, we are talking about 1,39 billions of pounds between 2007 and 2013. According to some studies, this number means that the EU contributed to 8,4% of the Northern Irish GDP (Giovannini, 2016). Will all this money disappear? If yes, what will be the consequence of the probable rising of the unemployment rate?

As we can see, there are question marks basically on every issue. In addition to this, the political situation in Northern Ireland is unstable. The power-sharing government between Sinn Féin and the Protestant DUP (Democratic Union Party) collapsed in January 2017 and new elections have been held on Thursday 2nd March. The two same parties won the majority of the seats and a new agreement between them will take time, giving more uncertainty to the entire picture. If an agreement is not reached in the next weeks, there is the concrete risk of new elections or, even more extreme option, the return of the “direct rule” of London (McDonald, 4/3/2017). In addition, a key leader of the peace process, Martin McGuiness, ex-IRA commander and Deputy First Minister of Norther Ireland for ten years until January 2017, recently died (McDonald, 21/3/2017).

All the above-mentioned issues can in a way or another be fixed through negotiations between UK, EU, Ireland and locals. A new status for Northern Ireland can be created and the majority of the problems solved. But the real problem lies somewhere else. In fact, what cannot be fixed is the core of the problem: the international position of Northern Ireland. In technical terms, we are facing a problem of indivisibility of stakes. In other words, Northern Ireland cannot be part of Ireland and be part of the United Kingdom at the same time. Until now, the problem was smoothed thanks to the fact that Ireland, Northern Ireland and UK shared a common future inside the European Union. But because of Brexit, this scenario does not exist anymore. Now a choice has to be made: Ireland or the United Kingdom. Black or white. And this decision will inevitably make some unhappy.

Considering that the force of inertia obviously pushes Northern Ireland to the United Kingdom, Sinn Féin becomes the central actor to analyze. It is unrealistic to think that they can just give up their main long-term political goal: the reunification of Ireland. It is simply something not acceptable for the majority of its constituencies. For this reason, the United Kingdom has to offer a framework to the Sinn Féin that leaves a door open for the reunification. However, these kind of arrangements are not easy to find. The easiest solution (that is also part of the GFA) would be the possibility of a referendum in the future. But who would decide when to hold it? And for how long would the result be binding? Five years? Ten years? Is it wise to use a referendum to settle a dispute which such as a problematic and violent history? Is it wise to divide further a community already divided with such a simple question?

Sinn Fein, Gerry Adams with delegates from the Sinn Féin Republican Youth National Congress 2017 at Free Derry Corner, 28/01/2017, CC BY 2.0

The only thing I am sure of is that a new agreement has to be reached and it has to clearly state solutions for the future. The status quo, without the possibility of reunification, would be extremely dangerous. In this situation, two scenarios could occur. In the first one, the Sinn Féin would radicalize its positions and close the doors to any kind of negotiations with the Protestant side. In this way, any power-sharing government (as included in the GFA) would become virtually impossible. On the contrary, if the Sinn Féin is perceived as too weak, there could be the risk of the rising of small but violent groups in the Republican side. The recent news of a bomb explosion at a police officer’s house in Derry/Londonderry is not a good sign (Deeney, 2017).

Luckily many factors push in the other direction. The economic dividends of peace have been huge for both communities. Moreover, many historical international sponsors of the Republican terrorism (such as Gaddafi’s Libya) do not exist anymore. More importantly, the Sinn Féin just elected its new leader in the Northern Ireland Assembly: Michelle O’Neill. She became a member of the party in 1998 after the Good Friday Agreement and therefore cannot be accused of being part of any paramilitary force active during the Troubles.

Even though the return of full-scale violence is extremely unlikely, the situation in Northern Ireland should not be underestimated. Winston Churchill said that “the Balkans produce more history than they consume”. This is also true for Northern Ireland. For this reason, it always better to hope for the best but still prepare for the worst.

Alessandro Fava

The blog is run independently of the Department of Peace and Conflict Research in Uppsala. The Pax et Bellum Editorial Board oversees and approves the publication of all posts, but the content reflects the authors’ own perspectives and opinions.

REFERENCES

- Ashtana, Anushka and Rowena Mason. “UK must leave European Convention on human rights, Theresa May says”. The Guardian. April 25, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/apr/25/uk-must-leave-european-convention-on-human-rights-theresa-may-eu-referendum (accessed February 22, 2017)

- Ashtana, Anushka, Daniel Boffey and Jessica Elgot. “UK to trigger Article 50 on 29 March, but faces delay on start of talks”. The Guardian. March 21, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/mar/20/theresa-may-to-trigger-article-50-on-29-march (accessed March 21, 2017)

- CAIN – Conflict Archive on the Internet. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/sutton/tables/Status_Summary.html (accessed February 22, 2017)

- Deeney, Donna. “Derry bomb: Culmore device at police officer’s home ‘more intricate’ than a basic pipe bomb”. Belfast Telegraph. February 22, 2017. http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/derry-bomb-culmore-device-at-police-officers-home-more-intricate-than-a-basic-pipe-bomb-35472857.html (accessed February 26, 2017)

- Giovannini, Arianna. “Il Brexit spacca il Regno Unito”. Limes 6 (2016): 65 – 76.

- Lundy, Derek. “Men that God Made Mad: A Journey Through Truth, Myth and Terror in Northern Ireland”. New York, Vintage, 2007.

- McDonald, Henry. “Northern Ireland election: DUP’s Arlene Foster ‘to stay as first minister”. The Guardian. March 4, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/mar/04/northern-ireland-election-dups-arlene-foster-to-stay-as-first-minister (accessed March 4, 2017)

- McDonald, Henry. “Martin McGuiness, Northern Ireland’s former deputy first minister, dies”. The Guardian. March 21, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/mar/21/martin-mcguinness-northern-ireland-former-deputy-first-minister-dies (accessed March 21, 2017)

- Mchugh, Michael. “Gerry Adams: Brexit will destroy the Good Friday Agreement”. The Independent. January 21, 2017. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/brexit-northern-ireland-gerry-adams-sinn-fein-good-friday-agreement-peace-eu-a7539011.html (accessed February 22, 2017)

- Worley, Will. “Theresa May ‘will campaign the European Convention Human Rights in 2020 election”. The Independent. December 29, 2016. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/theresa-may-campaign-leave-european-convention-on-human-rights-2020-general-election-brexit-a7499951.html (accessed February 22, 2017)